CDC didn’t take action as global health threats evolved

Beating disease is in the DNA of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a federal agency. During his first decade, this federal agency oversaw the eradication of smallpox, the eradication of malaria, and the eradication of polio as a threat to American health.

But as the 75-year-old organization’s director admitted this week, the CDC hasn’t evolved to keep up with the faster speeds and higher stakes of germs in the modern world.

Faced with the historic threat of the emergence of a new virus that has killed more than one million Americans, Dr. Rochelle Wallenski called on CDC employees to make changes, saying, “Our performance has certainly lived up to expectations. It wasn’t satisfying,” he said.

The official squeaky machine has already come under further criticism due to the monkeypox outbreak. If this doesn’t improve, experts say the public health institution that has long served as a global role model could disappear.

Newsletter

Get the FREE Coronavirus Today Newsletter

Sign up to get the latest news, best stories and what they mean to you, plus answers to your questions.

You may receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Many of these experts have spent much of the COVID-19 pandemic barely containing their dismay at the stalled efforts of government agencies to overcome early mistakes and restore the trust and confidence of Americans.

Now they have stopped trying to defend the CDC’s performance.

Lawrence Gostin, Georgetown’s public health law authority, said, “It’s a failed response to the greatest crisis of our lifetime.

The record of the mistakes that have resulted in “one of the biggest losses during this pandemic: trust in public health agencies,” says: Dr. Richard Besser, former CDC Director and current President and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

“It’s a culture that was just arrogant and overestimated what they were doing right,” said Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Center for Public Policy at the University of Pennsylvania and an expert on science communication.

As the novel coronavirus spreads around the world, the agency’s eminent experts have failed to detect it in early testing. They issued incorrect and confusing guidance on the value of face coverings. They took months to admit what outside scientists quickly gleaned: that the virus that causes COVID-19 spreads primarily through the air. It relied on epidemiological findings from Israel, Europe and South Africa instead of US data, which was often difficult to pull from the patchwork of overwhelmed public health departments responsible for the home.

The CDC’s announcements on basics such as how long to isolate infected people, who most urgently need vaccines and boosters, how long immunity lasts and what comes next have been delayed and garbled. They have been subject to warnings that ordinary Americans do not understand. When new findings called for an update to previous guidance, they dripped into the news cycle appropriately and without context.

“Frankly, we are to blame for making some pretty dramatic and pretty public mistakes,” Walensky said in a video distributed to the agency’s 11,000 employees. “We are suffering the consequences of these mistakes, from testing to data to communications.”

Neither the novelty of the virus nor political interference can excuse the CDC for a well-crafted debacle in the second and third years of the pandemic, she added.

“An honest and impartial reading of our recent history would lead to the same conclusion,” she said. “It’s time for the CDC to change.”

The CDC building at its headquarters in Atlanta.

(Ron Harris/Associated Press)

Wallenski’s sober approval follows a comprehensive review based on interviews with about 120 public health experts from inside and outside the agency.

In meetings with senior advisors and public health leaders, she listened to the culture of scientific narcissism. According to her, CDC epidemiologists acted with all the urgency of scientific conservatism and academic medical journals.

“By the time they’re done, the data could be bulletproof,” said a senior CDC official who wasn’t authorized to speak to the media. I did.”

The CDC’s risk communication mission is to embody three commands: be right Reliable. “But during the COVID-19 outbreak, the CDC was not the first and often lagged behind other sources and misinformation by a considerable amount of time,” Besser said. .

A top priority for Wallenski is improving the CDC’s ability to communicate scientific knowledge about health threats early, frequently, and authoritatively. Especially to Americans who need scientific knowledge to protect themselves and their communities.

“No one can say their message is current, clear, timely, or calm,” Gostin said. “They always seemed to be leading from behind.”

To a deeply divided public, the CDC’s altered guidance was often interpreted as a lack of belief or, worse, a manipulation. Many chose easier and more frequently updated sources for information about the pandemic.

But even scientists and public health experts — people who understood the scientific complexities of the CDC’s mission — have given up leadership of the agency, Gostin said.

Warenski tries to win them back with numerous proposals to modernize the agency.

This initiative is designed to strengthen partnerships between the agency’s workforce and healthcare providers and state and county public health agencies. They streamline data collection and sharing of CDC science.

This makes public health messages from government agencies faster and easier to understand when time is of the essence. Also, “no surprises” will be a key operating principle of CDC communications to avoid government crosstalk, which often makes the CDC seem ignorant.

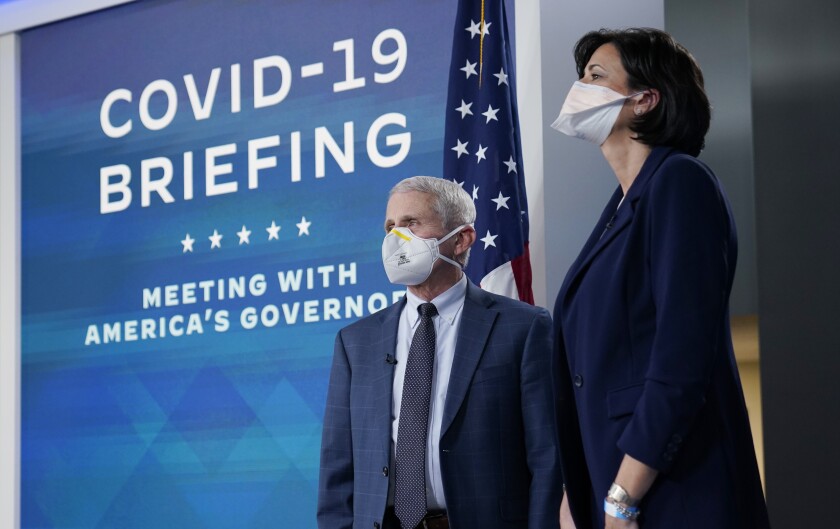

Dr. Rochelle Walensky stands with Dr. Anthony Fauci ahead of a regular conference call between the White House COVID-19 response team and the National Governors Association.

(Carolyn Custer/Associated Press)

Some changes, including the flexibility to move funds in an emergency, require congressional approval, a process that has already begun. Others, including the establishment of a new office for public communications and an agency-wide focus on diversity, equity and inclusion, just snapped in place.

And then there’s the challenge of developing the habit of agility.

“Yes, we plan to move some boxes on the org chart,” Walensky told CDC employees. You can’t stress that you can’t prepare for… change the culture.”

Certainly, the legal, budgetary and political constraints CDC has operated under will continue to present significant challenges, Gostin said.

In the decades before the emergence of COVID-19, steadily declining funding had hollowed out public health worker populations at the county, state, tribal, and federal levels. Shrinking budgets have depleted capacity in the kinds of labs needed for sudden outbreaks and hampered the introduction of new methods of monitoring public health, from genetic sequencing of virus specimens to wastewater monitoring.

The pandemic has underscored that these methods have taken hold, but the CDC still needs funding to build lab capacity and a workforce capable of practicing 21st century epidemiology. After billions of dollars have been spent on the pandemic, it may be difficult to sell to a wary Congress, Gostin said.

The CDC also needs to find more effective ways to manage data on new health threats, Gostin said. State and local governments, not federal agencies like the CDC, are responsible for implementing and enforcing measures to protect public health. A federal judge’s order this spring indicated that the CDC doesn’t even have the unquestionable authority to require people to wear masks on planes, trains, and other forms of public transportation.

Also, under the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Tenth Amendment, CDC cannot compel a state or county health department to collect and share data of public health interest if it does not want it.

This is a roadblock to the CDC’s pandemic response. At various times, various states, including Florida and Texas, failed to provide data on COVID-19 cases, vaccinations, and deaths, prompting federal agencies to speculate on missing figures or I had to do the math.

For the CDC to avoid such blind spots in future emergencies, it will need to create a surveillance system that links health care systems with ambitious states and counties, much like it does to monitor the flu. And we need to act quickly.

Lorien Abroms, who teaches public health communication strategies at George Washington University, is optimistic that the CDC can overcome the pandemic’s record of mistakes.

“Certainly they can reinvent themselves,” she said. I think we can definitely go back to that.”